How else can it be called?

Renal lithiasis

Nephrolithiasis

Urolithiasis

Renal calculi

ICD-10: N20

ICD-11: GB70.0

What are kidney stones?

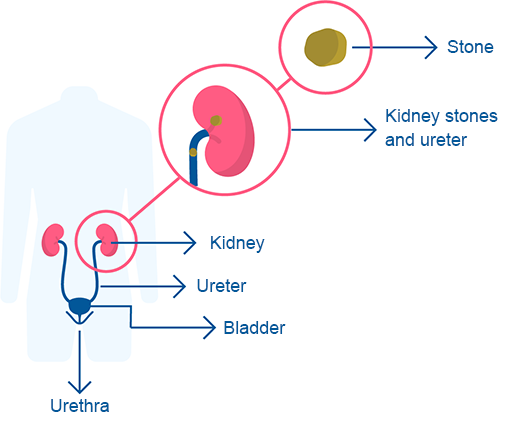

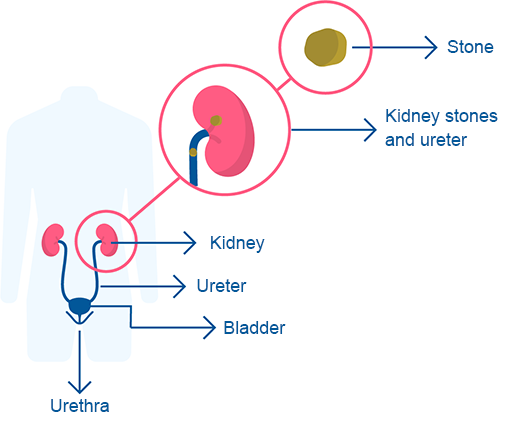

Renal lithiasis, also known as urolithiasis or nephrolithiasis, is a condition characterized by the presence of stones within the kidneys or urinary tract (including the ureters and bladder).

Kidney stones are solid masses composed of small crystals, which are normally present in urine. For various reasons, these crystals can become concentrated and solidify into larger or smaller fragments, forming solitary or multiple masses.

It is a common condition that affects more than 10% of the population, particularly in middle age. Men are more likely to develop kidney stones than women.

In recent years, the incidence of kidney stones has increased, largely due to the rising prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Early detection and treatment are crucial to prevent damage to the kidneys.

What types of kidney stones can be formed?

Kidney stones can be classified into different types, depending on the crystals that form them. Their causes and characteristics vary, and they may be influenced by factors such as the person's country of origin, although diet does not seem to have a significant impact.

The main types of kidney stones are:

- Calcium oxalate stones: Calcium can combine with other substances such as oxalate, phosphate, or carbonate (e.g., calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate). These stones are common in young people, especially men between the ages of 20 and 30. Their formation may be influenced by factors such as dehydration or genetic predisposition. Oxalate, found in various plant foods (such as chocolate, leafy greens, and tea), is often implicated, though the exact role it plays in stone formation remains unclear.

- Cystine stones: These are associated with cystinuria, a genetic disorder that affects both men and women. They typically develop in childhood.

- Struvite stones: These stones are caused by urinary tract infections, particularly those caused by Proteus bacteria. They are more common in women, due to the higher frequency of urinary tract infections in women. Struvite stones can grow very large, forming "staghorn" stones that can block the kidneys, ureters, or bladder.

- Uric acid stones: These stones are more common in men than women and can occur in individuals with gout or those undergoing chemotherapy. They form when the urine becomes very acidic.

- Magnesium ammonium phosphate stones: These stones are very aggressive, growing quickly, and are typically associated with kidney infections.

What are the main symptoms of kidney stones?

Kidney stones can cause a variety of symptoms, depending on their size, composition, and location within the urinary system. Some stones, due to their small size, may go unnoticed.

When a stone moves down the ureter and becomes trapped in narrower areas, it can lead to renal colic, a sudden and intense pain with the following characteristics:

- The pain may be felt in the abdominal area or on the side of the back.

- The pain may radiate to the groin (groin pain) or the testicles (testicular pain).

- The pain is so severe that it is often associated with nausea and vomiting.

In addition to renal colic, other symptoms may include:

- Recurrent urinary tract infections: These may cause dark or unusual-colored urine, a burning sensation when urinating (dysuria), and increased frequency of urination (pollakiuria).

- Hematuria (blood in the urine): This may be visible to the naked eye or detectable only through microscopic examination in a lab. It occurs due to the injury caused by the stone as it passes through the urinary tract.

Kidney stones typically do not cause fever.

How can kidney stones be detected?

In many cases, urinary stones do not cause symptoms and are discovered incidentally during an abdominal X-ray or ultrasound. Renal colic is the condition most likely to lead a doctor to suspect kidney stones, which must always be confirmed through tests such as:

- Blood tests: These are used to evaluate levels of calcium, phosphorus, uric acid, and other electrolytes.

- Kidney function tests: These include measurements of creatinine, creatinine clearance, urea, and other markers as defined by the urologist.

- Urinalysis: This test helps identify crystals and check for red blood cells in the urine.

To determine the location, size, and composition of the stones, as well as any associated conditions, the following diagnostic tests may be used:

- Abdominal x-ray: This is a useful and easy-to-perform test, especially in emergency settings. However, it does not detect uric acid stones.

- CT urogram: Once the gold standard for detecting stones, this test requires an intravenous contrast medium, which can be harmful to the kidneys.

- Kidney ultrasound: While not all stones are visible on ultrasound, it is particularly useful for detecting kidney damage, such as hydronephrosis (kidney dilation). Its major advantage is that it involves no radiation and can be used safely in children and pregnant women.

- Simple computed tomography (CT) scan: This is the most accurate and widely used test for diagnosing and monitoring urinary stones, but it is expensive.

The composition of stones that have been expelled is analyzed through specific laboratory tests. The presence of associated diseases is investigated later, based on the composition of the stones.

Which is the recommended treatment for kidney stones?

The treatment of renal colic has two main objectives:

Pain relief: This is typically managed with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), provided they are not contraindicated. In severe cases, opioids (such as morphine derivatives) may be used. Adequate hydration and antiemetic medications also assist in managing pain.

Stone expulsion: Stones that are smaller than 5 mm and near the ureter's exit are typically passed within 48 hours.

If the stones are large or if pain and vomiting cannot be controlled, hospitalization may be required. In such cases, one of the following procedures may be considered for stone removal:

- Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL): This method uses shock waves to break the stone into smaller fragments that can be more easily expelled in the urine. It is about 90% effective and is used for stones less than 1 cm in size that are located near the kidney or ureter.

- Endourology: This procedure involves making a puncture in the back at the kidney level or using the urinary ducts (urethra, bladder, etc.) to access the stone.

- Surgery: Surgery is only considered when other treatment options fail.

Follow-up treatment can focus on two aspects:

Staghorn stones, which occupy a large part of the kidney, must be removed surgically to prevent infections and kidney damage.

It is estimated that 40% of individuals will develop new stones within two to three years.

Follow-up care typically includes laboratory tests and imaging, depending on symptoms.

It is crucial to address associated conditions, particularly obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, as well as any deterioration in kidney function.

Bibliography

- First Aid for the Basic Sciences: Organ Systems (3rd Ed) 2017, Tao Le, William L. Hwang, Vinayak Muralidhar, Jared A. White and M. Scott Moore, ISBN: 978-1-25-958704-7, Pag. 636.

- Robbins Basic Pathology (10th Ed) 2018, Vinay Kumar, Abul K. Abbas, Jon C. Aster, ISBN: 978-0-323-35317-5, Pag. 576.

Rating Overview

Share your thoughts about this content